Erbil citadel

Erbil citadel is dramatically situated on top of a mound, or ‘tell’, of accumulated archaeological layers, visually dominating the modern city of Erbil, which radiates out from below in concentric rings of expansion.

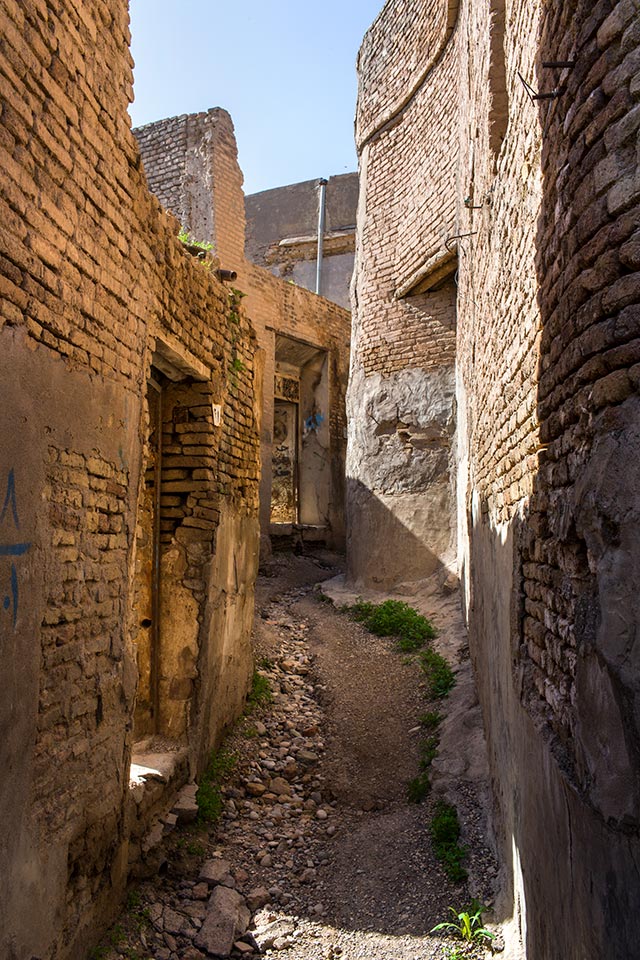

Believed to have been in existence for at least 6,000 years, Erbil claims to be the oldest continuously inhabited city in the world. The current buildings on the uppermost layer of the tell date back to the mid-18th century. The urban fabric however reflects a much older pattern, as individual buildings have been levelled and rebuilt on the same site over successive eras, the process which also caused the tell to grow from the surrounding plain.

In 2007, the High Commission for Erbil Citadel Revitalisation (HCECR ) was established by the Kurdish Regional Government to protect and restore the citadel. The remaining 840 families were resettled, leaving just one family to hold on to Erbil’s claim of being the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city. The citadel was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in June 2014.