The perimeter walls of Erbil citadel viewed from below the ‘tell’.

Richard Wilding, 2013

Return to Kurdistan

Richard Wilding in conversation with Tom Bilson, Head of Digital Media at the Courtauld Institute of Art

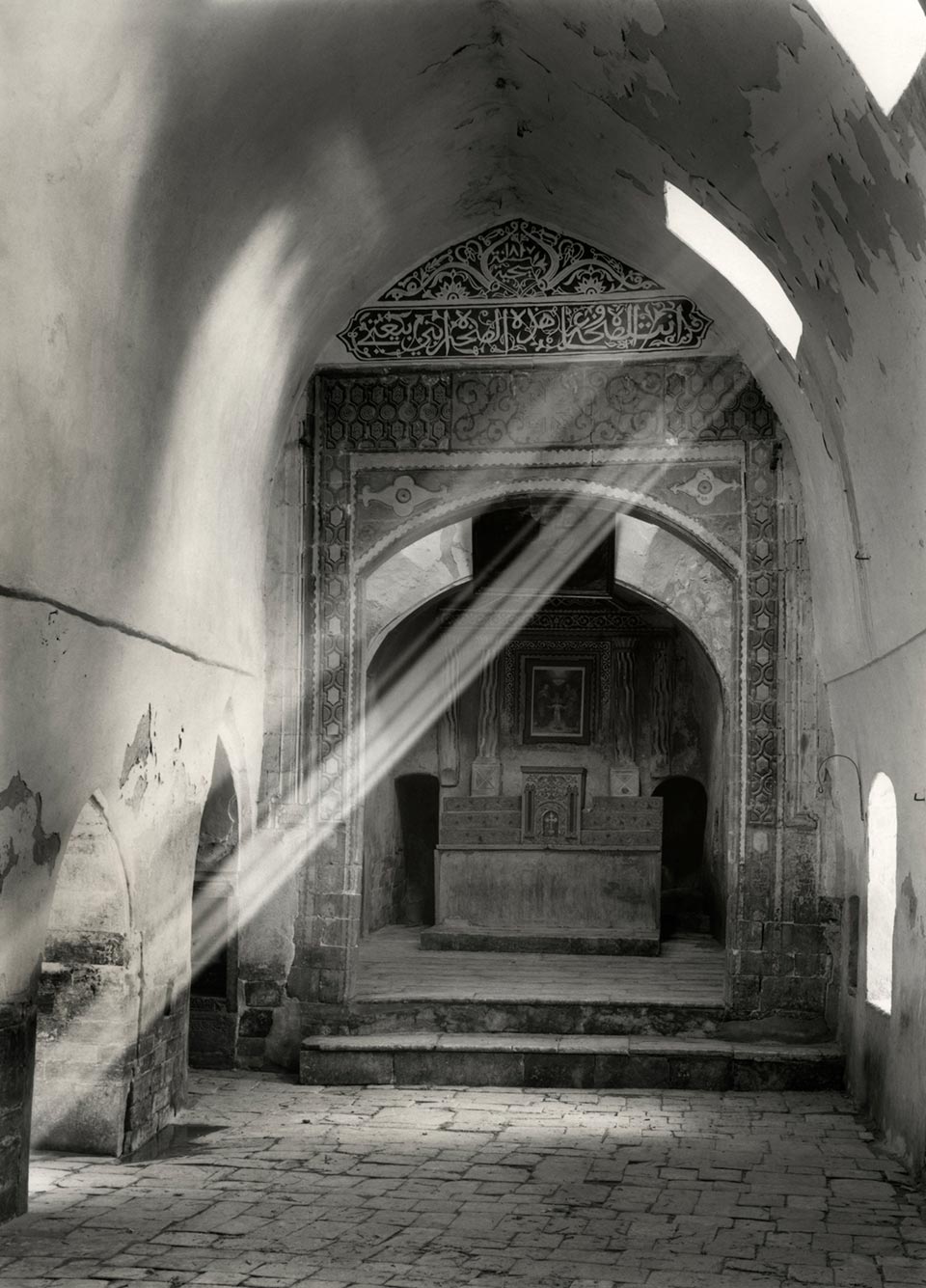

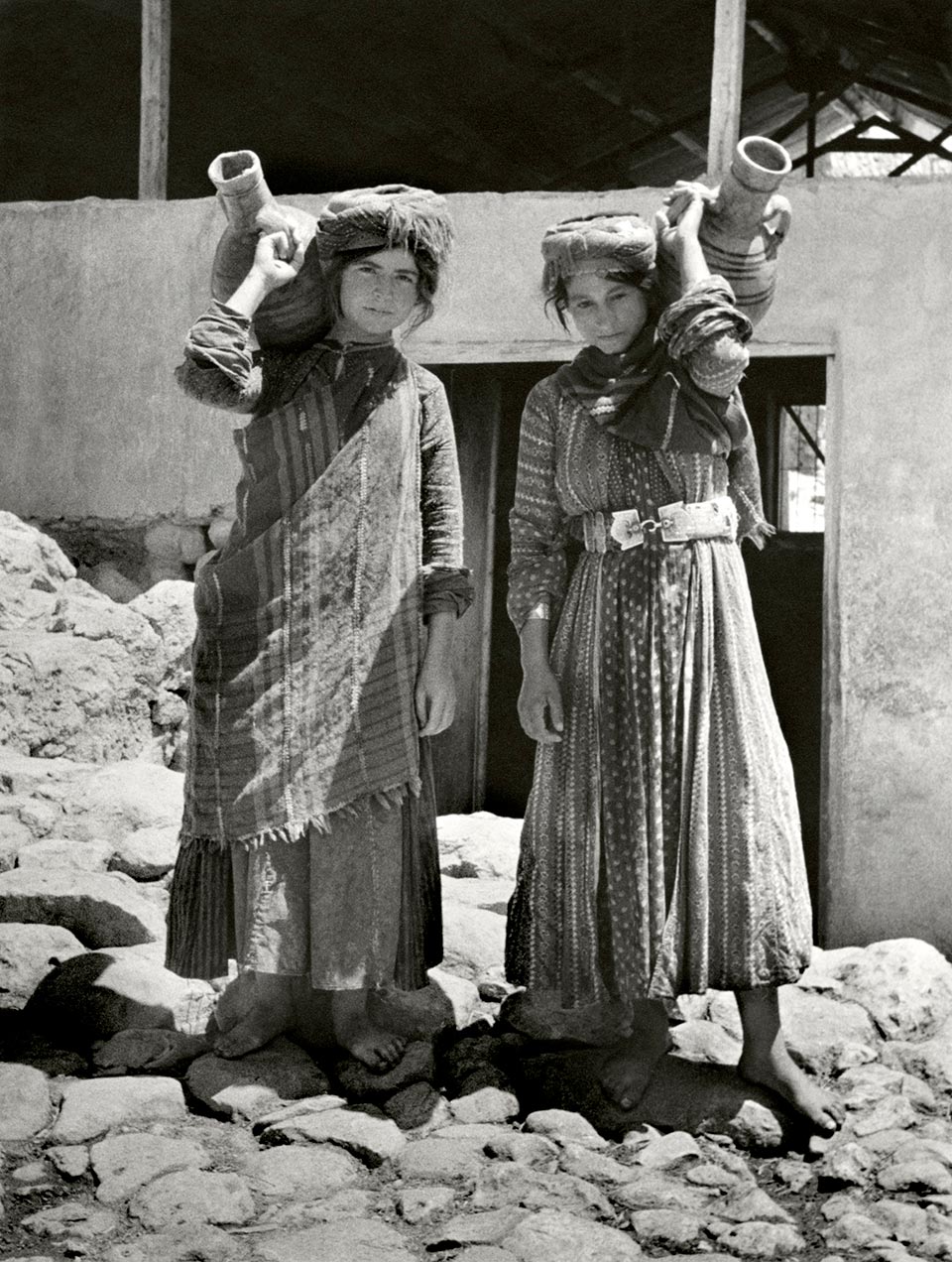

During May 2016, Richard Wilding mounted exhibitions of his photography in the cities of Erbil and Sulaymaniyah in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Alongside his contemporary colour photographs of Kurdistan and Northern Iraq, Richard also included black and white photographs taken by Anthony Kersting in the 1940s. These were reproduced from Kersting’s original prints and negatives held in the Courtauld Institute of Art’s Conway library.

Richard is a London based producer and photographer working internationally with museums, charities and governments on exhibitions, websites and printed publications. He specialises in the documentation of archaeology, heritage and cultural identity and is engaged in long-term projects in Kurdistan, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, in addition to ongoing consultancy work in the UK.

Since 2012, Richard has been Creative Director of Gulan, a UK registered charity which promotes the culture of Kurdistan to an international audience. They have organised a series of events celebrating the cultural, ethnic and religious diversity of the Kurdistan region of Iraq. Exhibitions presented by Gulan at the Royal Geographical Society and the British Academy in London have included Anthony Kersting’s photographs to illustrate this rich history and culture.